The Spookier School: (Anti-)Surrealism in Glasgow

This paper poses the question ‘What is Surrealism?’ from a particular vantage point: that of a practicing artist who has lived and worked in Glasgow since the turn of the twenty-first century. With reference to my own art practice, I will consider my troubled relationship with the category ‘Surrealism,’ as contingent with the specific trends of the Glasgow art-scene during this period and the broader international context.

In particular, I will address the apparent interest in surrealist methods demonstrated by Glasgow-based artists in the early 2000s (in opposition to the neo-conceptual and relational aesthetic genres that had placed prominent Glasgow artists on the international map in the previous decade). Whilst acknowledging the value of research into the historical surrealist movement (for shaping a more rigorous understanding of my practice), I will also recount my frustrations with the movement as they emerge in two areas: doubt regarding the ‘revolutionary’ power of the unconscious, and the potential valorisation of ‘linear’ narrative thinking – even in the domain of the ‘fantastic’.

The name ‘Spook School’ was given to the Glasgow Four, a group of designers at the turn of the twentieth century, whose elongated figures and elaborate distortions of form were thought eccentric and even macabre by some of their contemporaries. The Four, consisting of Margaret MacDonald, and her sister Frances, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and his friend Herbert McNair, shaped the aesthetic of Glasgow art-nouveau.

I first became aware of the term in the early 2000s—as a student in my final year at The Glasgow School of Art conducting tours around the Mackintosh Building. And I’m still unsure whether this (and not Surrealism) might be the original inspiration for the distorted figures that subsequently appeared in my own drawings.

Frances Macdonald McNair, Ill Omen, 1893, pencil and watercolour on paper, 51.7 x 42.7cm, Glasgow, Hunterian Museum

But Art Nouveau (the international movement to which the ‘Spook School’ subscribed, and to which they added a visionary touch mined from the Scottish vernacular style and an eerie Celtic sensibility) is a recognised influence on surrealist art (for example on the work of Salvador Dalí), and this raises an interesting challenge when trying to categorise my own and other artists’ work from the millennial epoch. When a ‘dream-like’ sensibility rears its head, are we in the presence of Surrealism (as defined by the movement’s founder André Breton in 1924), or are we looking at the trace of older historical movements, from which it borrowed stylistic traits; or indeed subsequent cultural phenomena which emerged from Surrealism or plundered the movement for their own ends (cartoons, Psychedelia, or other forms of mellifluous pop culture)?

I probably became aware of the adjective ‘surrealist’ (as a pejorative term) in roughly the same period that I learned about the ‘Spook School’. Whether consciously or not, my tutors in the Drawing and Painting Department at The Glasgow School of Art were paraphrasing the Greenbergian prejudice, acutely summarised by Hal Foster in his book Compulsive Beauty a revisionist account of the Surrealist uncanny published in 1993. According to such prejudice, Surrealism had been dismissed as:‘improperly visual and impertinently literal’, ‘not properly modernist at all,’ ‘corrupt’, ‘technically kitschy’, and ‘hypocritically elitist’ (Foster, 1997: xii).

Certainly, this seemed to be the general feeling at The Glasgow School of Art where I undertook my formal education in the late 1990’s (graduating in 2001). The school pedagogy was at that time dominated by the neo-conceptual approach perhaps especially by Glasgow’s contribution to this genre, and by socially engaged ‘relational’ art which involved direct intervention in public space. These trends, exemplified by such artists as Douglas Gordon, Christine Borland, Roderick Buchannan, Nathan Coley and Martin Boyce, supplanted the previous Glasgow success story, associated with painters like Stephen Campbell and Adrien Wizneskie (whose work often held a strong surrealist flavour).

Indeed, as a student, I was warned away from anything that resembled Campbell or the so-called ‘New Image Painting’. Instead, a cooler, more rational, even academic approach was favoured; either the abandonment of painting altogether, or the use of painting itself as a conceptual tool, deployed to visualise art theory or specific sociological ‘research’. As the Edinburgh-based art historian Neil Mulholland observed in his essay ‘Learning from Glasvegas’ (published in 2002), this was the lauded manifestation of Scottish Contemporary art at this time, admired for ‘the rigour of its research and for the formal rigour it derived from the international style [of architecture and design]’ (Mullholland, 2002: 64).

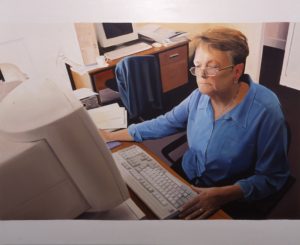

Janice McNab, Grace in The Employment Rights Office, 2001, oil on board, 122 x 150cm, ©Janice McNab

In this context, the kitschy psychoanalysis of Surrealism was decidedly out of favour. And for a while I succumbed to this prejudice, moving away from anything that might be thought of as embarrassingly occult. After graduating, however, I wanted to interrogate this taboo. The desire to challenge this orthodoxy coincided with an arguable ‘surrealist’ turn in the works of some emerging Glasgow-based artists in this period, including those with whom I engaged in extensive discussion and collaboration. This was the period in which I first began to practice as an artist in Glasgow, undertaking exhibitions locally, writing about Glasgow-based contemporary art as a reviewer and commissioned writer, and engaging in curatorial practice in my role as a Committee-member for Transmission gallery (the artist-led exhibition space).

At this time, the conceptual approach, which had dominated my art-school education, appeared to be challenged by a renewed interest in methods that might be understood to have their roots in surrealist practices of the 1920s and 30s. These methods included: the objèt-trouvé (not the Duchampian ready-made, but the more uncanny adaptation of resonant found objects, in the tradition of Man Ray, Meret Oppenheim and Dalí); metamorphic imagery; the use of chance and accidental processes in making; and the use of collage to create improbable spaces and visual non-sequiturs.

Iain Hetherington, Design for a Monument to Sir Francis Galton, 2008, oil on canvas, 66 x 76.2 cm

At the same time, the use of forms, materials and approaches that seem very suggestive of surrealist art went hand-in-hand with a broadly held scepticism regarding its central philosophy: namely, the idea that a release of the unconscious and of ‘repressed desires’ could lead to social and political revolution.

In 2002, Adam Curtis’s documentary film The Century of the Self (detailing the influence of Freud on advertising via Edward Burnais) helped propagate the view that animating repressed desire had become a device of capitalism (had entangled the social subject deeper in its imperatives as opposed to providing any liberation from those constraints). The idea that art engaged with Freudian concepts (however subversively) could bring about revolutionary social change was coloured by these broader observations, typified by Slavoj Žižek’s famous pronouncement, derived from Jacques Lacan: that the hedonist pursuit of pleasure was a duty not a rebellion under late capitalism (see Žižek, 2008: 44). Even positive re-appraisals of Surrealism by art historians and critics questioned this fundamental premise of the movement. And this might explain why Glasgow-based artists, working in this period, tended to avoid citing the movement verbally (for example in interviews and statements), even when seeming to emulate its methods.

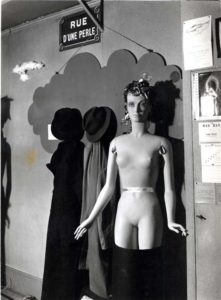

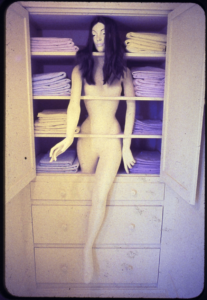

As a result, there is some taxonomic confusion when addressing the art that emerged from Glasgow in the first decade of the 21st century. Were the shop-window mannequins deployed by Cathy Wilkes in her 2005 installation for ‘Scotland & Venice’ a nod to Breton’s concept of ‘the Marvellous’ (and the broader surrealist fascination with prosthetics and dolls)? Or was this a gesture in thrall to second wave feminist art, for example Sandy Orgel’s Linen Closet work for the California WomanHouse (1972)?

Cathy Wilkes, Non Verbal, 2005, mixed media, dimensions variable © The Modern Institute/ Toby Webster Ltd.

Man Ray, Mannequin de l’exposition Surrealist, 1938 , 1938, gelatin silver print, 23.8 x 14.91 cm (printed circa 1966)

Sandy Orgel, Womanhouse: Linen Closet, 1972, mixed media, dimensions variable

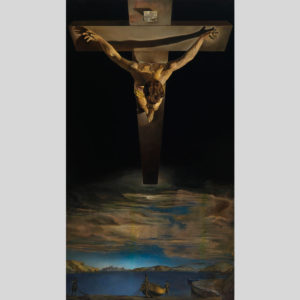

In spite of these dilemmas, I found I did want to know more about Surrealism and understand its influence on my own practice and that of my peers. It should be acknowledged that many of my first-hand encounters with surrealist art occurred in Glasgow and Edinburgh—for example, Dalí’s Christ Saint John of the Cross (1951), housed in the St Mungo’s Museum of Life and Art when I first arrived in Glasgow (in 1997), formed the subject for my first undergraduate essay.

But, in the early 2000s, it was hard to believe that subversive art of the past could be politically subversive in the present (or that aesthetic subversion could be politically progressive, at least from a soci-economic perspective). Glasgow at the turn of the millennium was a prime location to experience these contradictions. A sprawling post-industrial city, containing the relics of its nineteenth-century past (its spoils of Victorian expansion, colonialism and empire) its medieval ecclesiastical architecture and modernist failed utopias; a city of exquisite ruins, that might have appealed to André Breton—and to Walter Benjamin (whose study of nineteenth-century Paris arcades had been inspired by the surrealist writer, Louis Aragon).

Salvador Dalí, Christ of St John of the Cross, 1951, oil on canvas, 204.8 x 115.9 cm, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow, © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection

But this city of ruins was also the location of extreme social/economic privation —for example in Site Hill, an area of the city where I worked as a library assistant for a number of years and where a large number of asylum seekers were housed in the partially-abandoned tower blocks. And the visible fact of that privation (and its human cost) contrasted somewhat brutally with the internationalist glamour of the ‘Art World’—what has been called ‘The Glasgow Miracle’.

The first decade of the twenty-first century saw a dizzying expansion of a locally based commercial scene, with four new galleries opening in the city. Buoyed by National Lottery and Scottish Arts Council funding, this commercial scene (in the spirit of New Labour cultural policy) brought a feeling of efficacy and optimism to some artists living and working in the city and drew energy from a vibrant public discourse around contemporary art, enflamed by the YBA’s in the previous decade. This was the context in which I discovered Surrealism, sometimes in sympathy, sometimes in opposition to its forms.

One of the dilemmas I encountered was how to reconcile the aesthetics and philosophy of that movement with the business of ‘telling stories’ through (and in conjunction with) visual art. I had formed a connection with Surrealism because it seemed to validate the role of fiction in visual art, at a time when narrative painting was perceived as anachronistic and crudely populist. With its connection to Freudian psychoanalysis and sometimes to classical mythology, its manifestation in bibliographic form (for example in the work of Max Ernst), Surrealism did provide a link to the fantastic imagination, and also to the pleasure of inventing new narratives through a disruptive process.

But Surrealism, though derided for its literary and occultist tendencies by Clement Greenberg, was also precarious as a conduit of fiction (in the classical sense). The archetypal surrealist narrative whether visual, cinematic or verbal is an immaculate corpse, a linked series of none-sequiturs and ruptured images designed to simulate the actual workings of the unconscious—the Freudian dream work. This model, radical and inspiring in the 1920s and 30s, had become rather tired by the early 2000s.

Merlin Carpenter, Chairs, 1999-2000, Acrylic on canvas, 195 x 360 cm, © the artist and Simon Lee

The appropriational monster of post-modern art was largely to blame for this impasse. It had become standard in figurative painting for diverse images (often culled from popular culture) to be overlaid in an apparently random fashion, suggesting an absolute relativism and absence of meaning. These neo-avant-garde gestures were set against a broader culture of pastiche, quotation and anachronism (in music videos, billboard adverts, and fashion editorials) that has only accelerated online. The liberation offered by surrealist methodology, was thus undermined by a suspicion that the unconscious in its purity might yield something devoid of productive meaning, of genuinely critical energy and purpose.

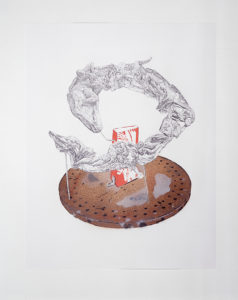

The artist Clare Stephenson who has lived and worked in Glasgow since the late 1990s, responded to this deadlock by mobilising the technique of post-modern (or surrealist) collage in a more analytical way. In 2003-6 she produced a series of spray-paint and pencil drawings incorporating visual quotations from sculpture, including from Canova’s eighteenth-century classical forms and Daumier’s satirical maquettes, juxtaposed with miniature constructions she had made herself from found objects. These 2-dimensional collages were presented as much as possible as if they could exist in real physical space. As the artist explained in conversation with me in 2004, the objects portrayed in the drawings were as much informed by problems of support, weight, and balance as if they were blueprints for sculpture; the acknowledgement of ‘material consequence’ ensuring against the ‘crappy formalism’ of random pictorial motifs.

Clare Stephenson, Eels, 2004, pencil and spray-paint on paper, 84 x 59 cm

If the weight and balance of sculpture—the ‘material consequence’ of gravity, in other-words—provided the crux of Stephenson’s approach to collage-form (the means by which to give structure to a play of images), the much-maligned ‘linear narrative’ (often explored through sequential ‘storyboards’) gave substance to my own exploration of surrealist methods.

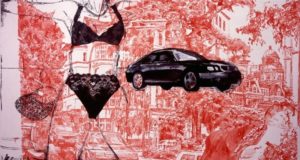

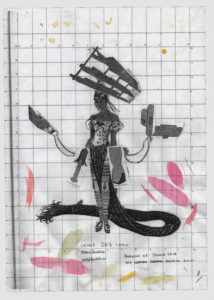

Laurence Figgis, Untitled Collage, 2002, digital print , ink, pencil, watercolour on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm

It helped me to think of my collaged figures as characters, players in a drama, and to think of their movements and behaviour as subject to material constriction. These pressures (manifesting as visual signs of distortion / metamorphosis) reveal the weight of authority— the limits imposed by social, economic, and gender hierarchies and by the body in its vulnerability. In this view, surrealist methods change their implication, no longer signifying ‘freedom’, as such, but the (violent) impact of power-relations. This is how transformation signifies in fairy tales and classical myths, and in some examples of surrealist art— especially at the intersection of surrealist methodology, class analysis, and feminist and queer subjectivities.

To that end, some of the most exciting academic work on Surrealism, by art historians based in Scotland was undertaken in relation to women artists connected with the movement. The art historian Catriona McAra has explored the link between Surrealism and other types of fantasy literature, specifically the anti-tale: a genre of subversive fairy tale that had been mobilised for the purpose of Marxist-feminist critique by Angela Carter in the 1970s and 80s and more recently by such visionary writers as Kate Bernheimer. This analogy was the focus of two symposia that McAra participated in organising at The University of Glasgow in the late zeros, both of which I attended as a speaker or delegate: Arts to Enchant (2009) and The Uses of Disenchantment (2010).

In an essay of 2013, comparing two artists connected to the Surrealist movement, Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington, with Angela Carter, McAra posits that all three …’stand for the renegotiation of feminism in Surrealism by drawing on and re-visioning its violent aesthetic’. As she writes, ‘through reconciling text and image, real and sur-real, literal and metaphorical’, the surrealist imaginary becomes ‘critically self-conscious and moves off the page or canvas into the perpetual struggle and reality of body politics’ (McAra, 2013: 86).

An equivalent ‘violent’, transformational aesthetic allowed me to respond to my own immediate cultural context; that of a gay artist living and working in Glasgow at the turn of the twenty-first century, bearing witness to art’s capture as an agent of the neoliberal economy, and its visible signs of tension and collapse as it moved against these contradictory ideologies.

Works cited:

Foster, H. (1997), Compulsive Beauty, Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press.

McAra, C. (2013), ‘Sadeian Women: Erotic Violence in the Surrealist Spectacle’, in Violence and the Limits of Representation, Matthews G., Goodman S. (eds), London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 69-89.

Mulholland, N. (2002), ‘Learning from Glasvegas: Scottish art after the ‘90’, Journal of the Scottish society for Art History, Volume 7, 2002, pp. 61-70.

Žižek, S. (2008), In Defense of Lost Causes, London; New York: Verso.

This paper was delivered at the Association for Art Historians Annual Conference, 2021, as part of the panel ‘Surrealism and Scotland,’ convened by Professor Susannah Thompson, Professor Patricia Allmer and Dr Gráinne Rice