Exhibition Flyer

Exhibited Works

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Amuse the Corpus-Total, 2015, acrylic, gouache, pasted paper on paper mounted on foam-board, 29.8 x 42 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

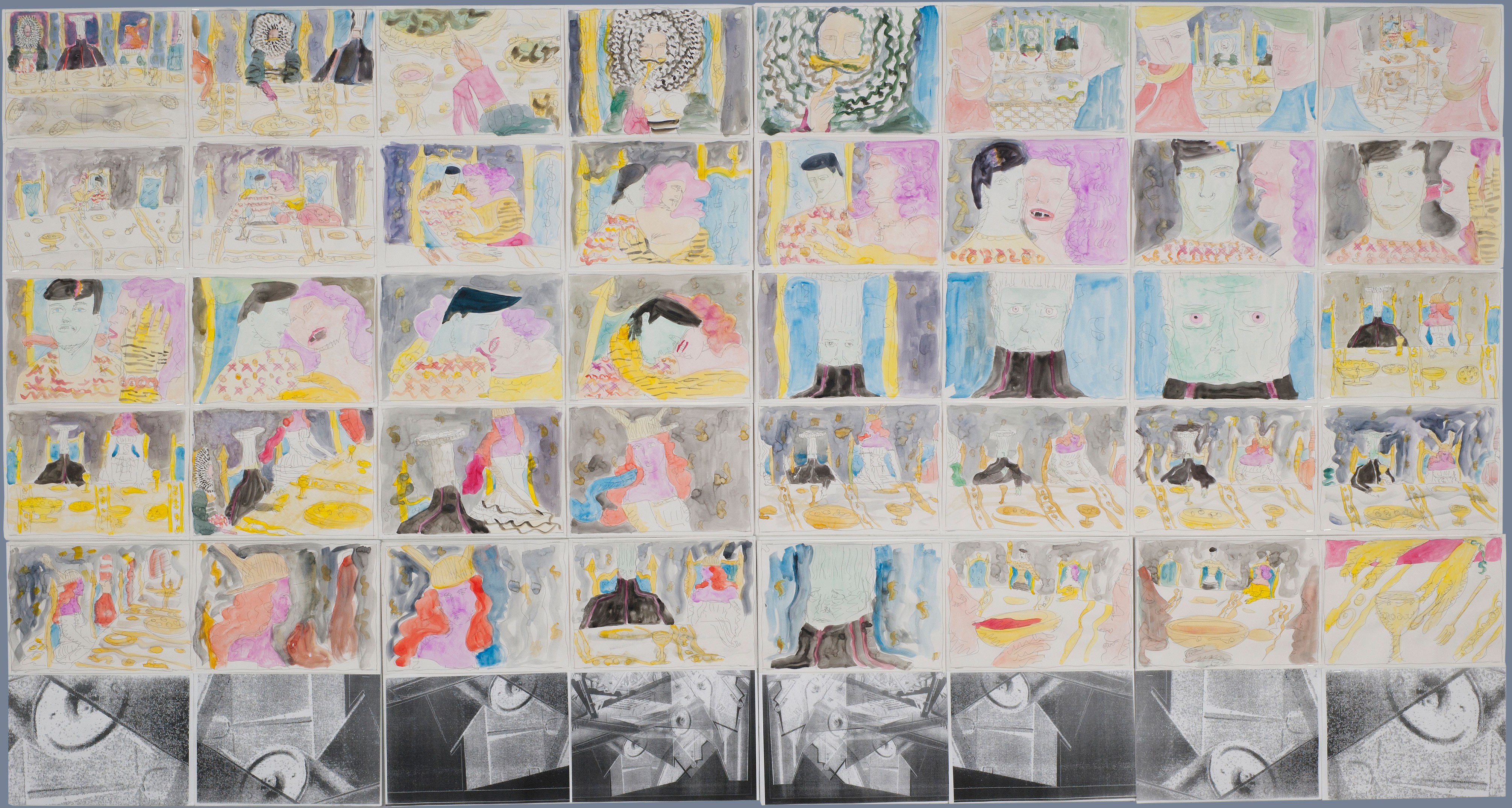

Laurence Figgis, Hall of Solid-Profit, 2015, ink, watercolour, digital print on paper, mounted on foam-board, 126.1 x 237.8 cm, Laurence Figgis

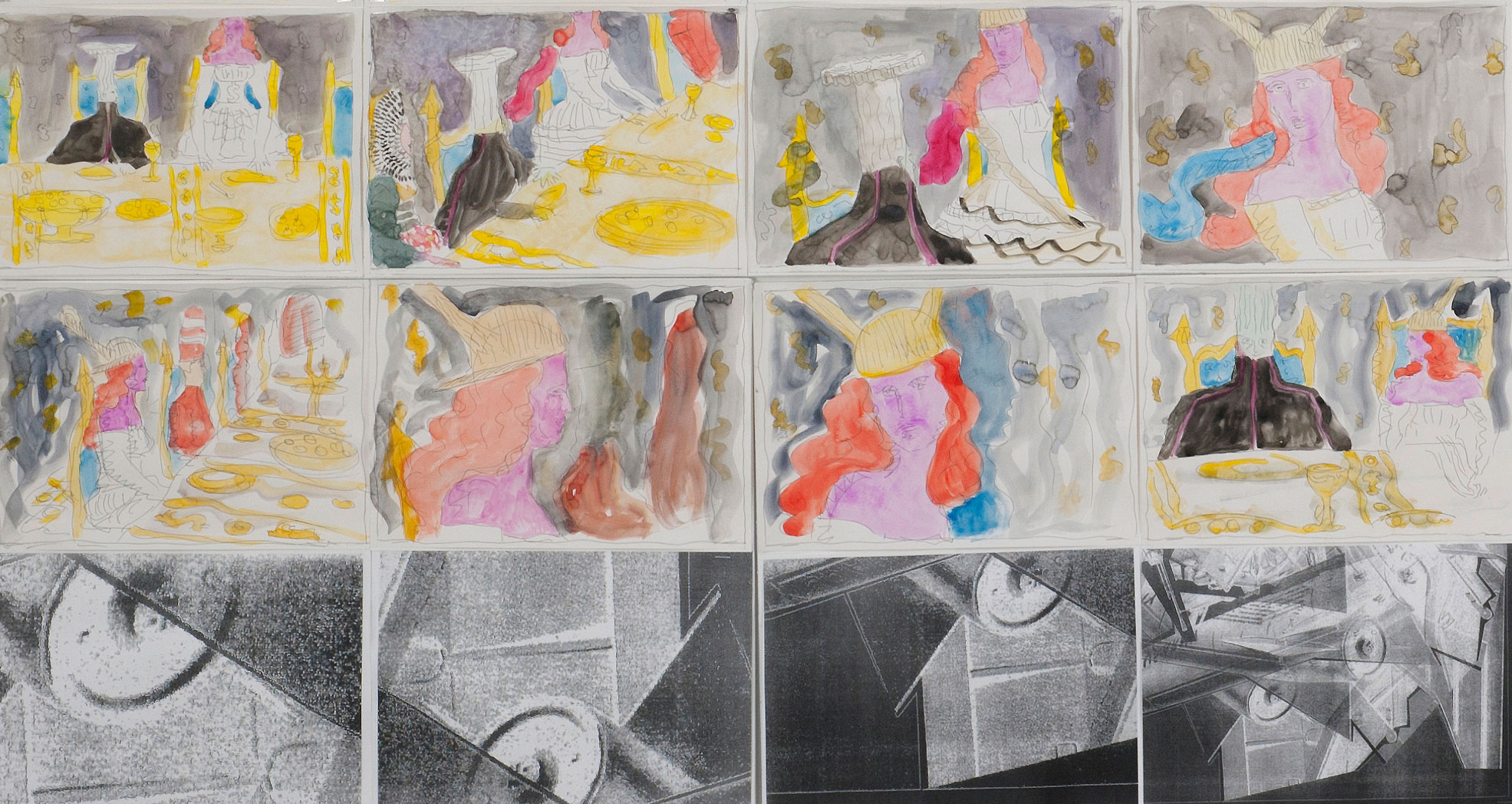

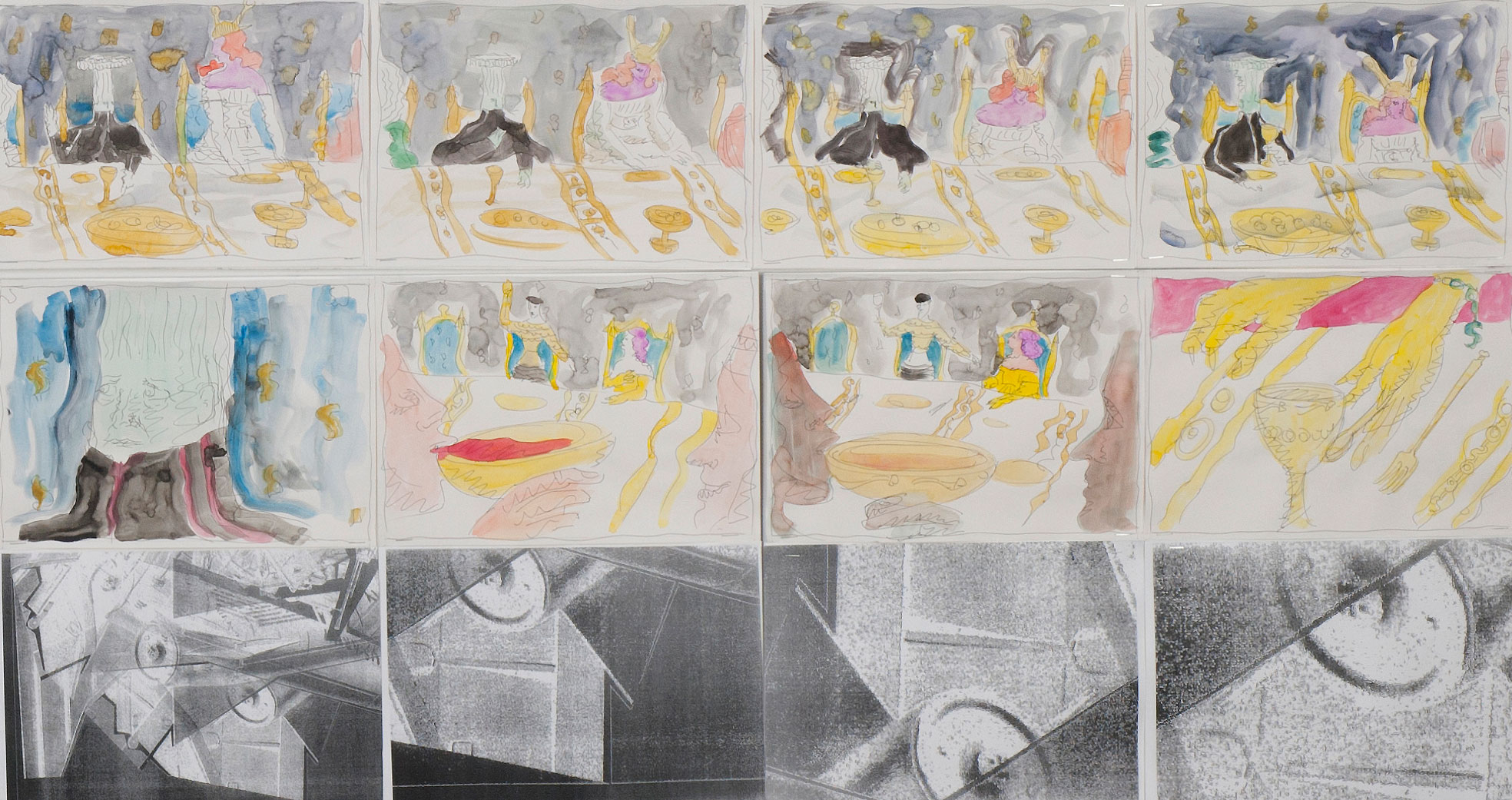

Laurence Figgis, Hall of Solid-Profit (detail), 2015, ink, watercolour, digital print on paper, mounted on foam-board, 126.1 x 237.8 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Hall of Solid-Profit (detail), 2015, ink, watercolour, digital print on paper, mounted on foam-board, 126.1 x 237.8 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Hall of Solid-Profit (detail), 2015, ink, watercolour, digital print on paper, mounted on foam-board, 126.1 x 237.8 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Hall of Solid-Profit (detail), 2015, ink, watercolour, digital print on paper, mounted on foam-board, 126.1 x 237.8 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

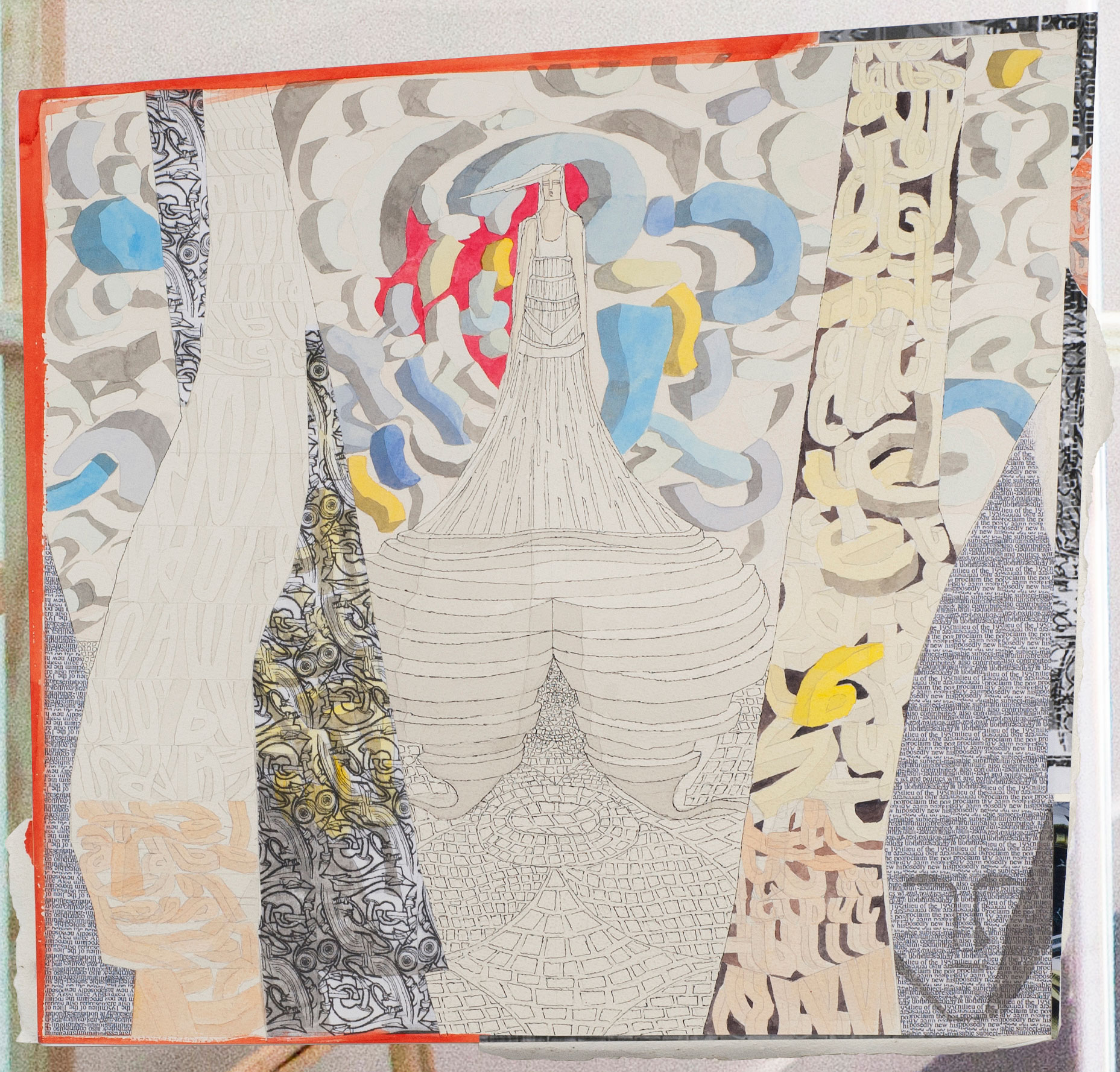

Laurence Figgis, Bill-Deed, 2015, pencil, ink, watercolour, collage on paper mounted on foam-board, 45.8 x 44.6 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, And she would Whisper, 2015, acrylic on paper mounted on foam-board, 51.7 x 73.9 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, True Sectarian Then, 2015, gouache, acrylic on paper mounted on foam-board, 41.9 x 29.8 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled, 2015, pencil, watercolour, gouache on paper, staples, masking-tape, 59 x 16 cm, photograph by Alan Dimmick, ©A Dimmick, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled (dress for Styrene), 2015, gouache, acrylic, ink on paper, staples, dress-maker’s dummy (wood, polystyrene), 149 x 78 x 64 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled (dress for Styrene), 2015, gouache, acrylic, ink on paper, staples, dress-maker’s dummy (wood, polystyrene), 149 x 78 x 64 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled (dress for Styrene), 2015, gouache, acrylic, ink on paper, staples, dress-maker’s dummy (wood, polystyrene), 149 x 78 x 64 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled (dress for Styrene) (detail), 2015, gouache, acrylic, ink on paper, staples, dress-maker’s dummy (wood, polystyrene), 149 x 78 x 64 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, Untitled (dress for Styrene), 2015, gouache, acrylic, ink on paper, staples, dress-maker’s dummy (wood, polystyrene), 149 x 78 x 64 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, They Kents, 2015, acrylic on paper mounted on foam-board, painted wood frame, 42 x 30 cm, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

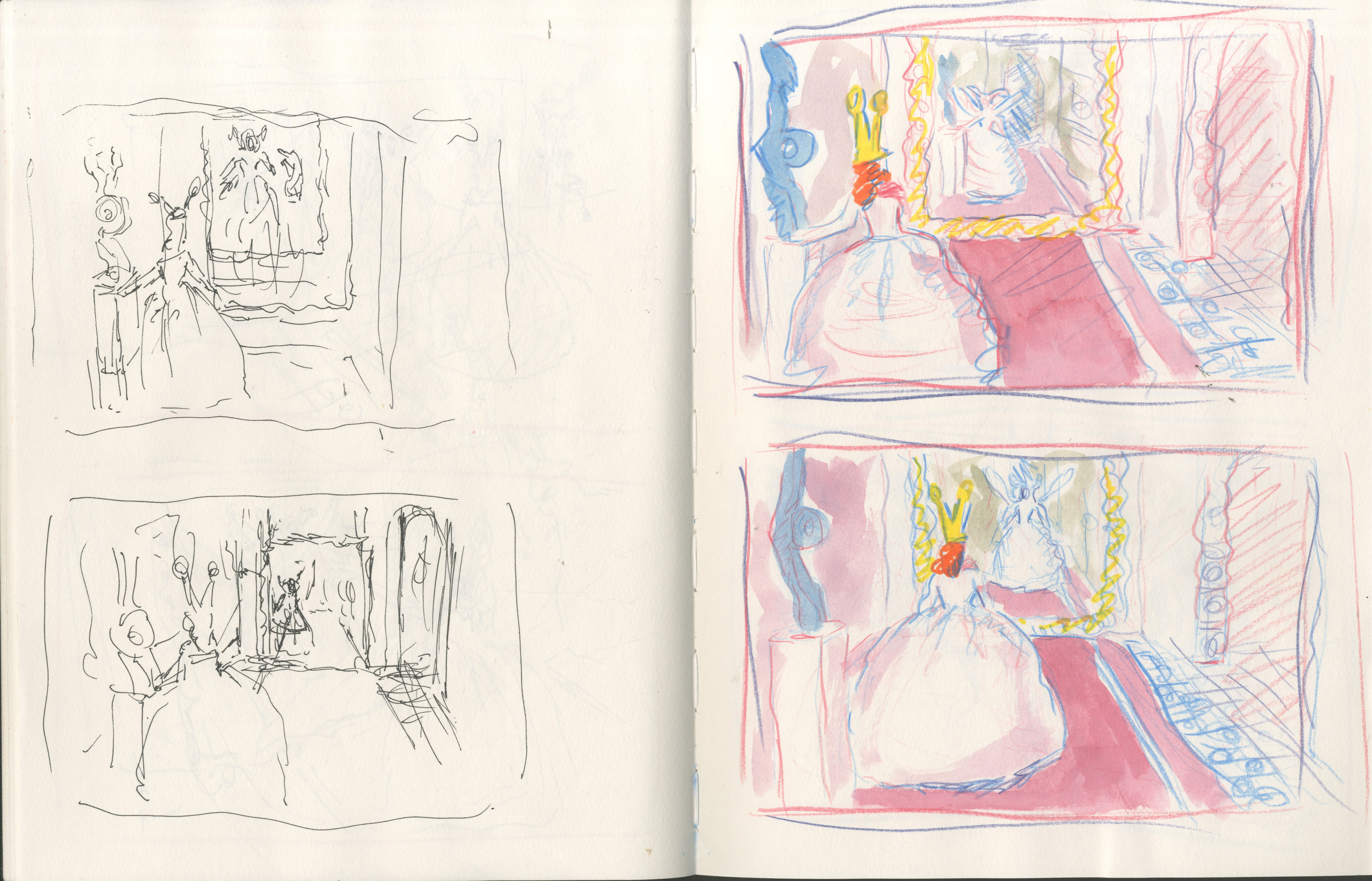

Laurence Figgis, Hugs Athener, 2014, ink, watercolour, crayon on sketchbook page, 28 x 43 cm, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Laurence Figgis, ‘ANYKENT’, The Briggait, Glasgow, 2015, exhibition installation view, photographed by Jenny Wicks, ©Jenny Wicks, ©Laurence Figgis

Exhibition Texts

‘Anykent’ by Laurence Figgis

the seagull is himself enchanted by

the sound of hades and the lumpenboo,

a busting-boo in rhythm to the cry

of boom and bust and bust and boo

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my seagull-you

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my lumpenboo, lumpenboo

bring me all the birds for rent, and bring me

all their debt, for death is kind to those who

want and brings them all the passion of their

rent – and eats them to be eaten too, and

so to eat my gull, and damn this corny

bird–head rises when I try to knock it

down, I’ll choke it, choke it, stuff its feathers

in my mouth, and bring the banking house down

for your ‘very valid’ love, and bring the

banking-house down for your pimp and prostiboo

and bring the banking-house down for your

elle-a-chaud-au-cul (like the bank-and-void)

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my seagull-you

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my lumpenboo, lumpenboo

and what are u? the gull replied,

a good-for-naught but death’s emploi–

a VERY-VALID bank-and-void,

a lumpen en–bourgeois, and you will feel so

sad for him, you lay ure thoughts out on the

tar, my brains for thee, un-bothered cogs, the

wheels, the wheels, the wheels of hades’ shining car

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my seagull-you

you are my kent, you are my kent, you are my lumpenboo, lumpenboo

©Laurence Figgis 2015

Compendium

‘Although the sphinx has leapt up on Oedipus and dug her lioness claws into his bare flesh, her face looks no more menacing than the young Queen Victoria’s as seen in profile on a coin of the realm. There is no sense that she is threatening his very life instead of one of his sartorial whims. As Degas said, “He would have us believe the gods wore watch-chains”. The background is made up of a “praline landscape” and a “rock candy mountain”.’ (White, 2000: 141)

Edmund White, The Flâneur

‘Anachronism is, on the contrary, a real and living thing, a thing having flesh and bones. It would be enough to surprise us in a moment of sentimental distraction in order to leave in our flesh and our memories a mark of the real bites of poetry, and in order to rip out from us, with the slashing claw of anxiety, one of the most nutritious pieces of our intellectual anatomy.’ (Dalí, 1998: 253-4)

Salvador Dalí, ‘The Latest Modes of Intellectual Stimulation for the Summer of 1934’

‘In reality they all lived in a kind of hieroglyphic world, where the real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs.’ (Wharton, 2006: 44)

Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

‘It is the myth of how culture came about, and of how society occurred. Because it is so ambitious a myth, it has the puzzling self-containment of a mystery in the old sense of that word. At the same time because it is so prosaic a myth (a myth about crinolines!) it is not in the least portentous or self-consciously “mythic”.’ (Gilbert, 2000: 256-7)

Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic

‘Many counties, I believe, are called the garden of England, as well as Surrey.’ (Austen, 1975: 276)

Jane Austen, Emma

References

Austen, Jane. Emma. (London: Harmondsworth, 1975).

Dalí, Salvador. The Collected Writings of Salvador Dalí, ed. and trans. Haim Finklestein. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, 2nd ed. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2000).

Wharton, Edith. The Age of Innocence. (London: Penguin, 2006).

White, Edmund. The Flâneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris. (London: Bloomsbury, 2001).

Further Reading

Review of ‘ANYKENT’ by Adam Benmakhlouf

This review was published in The Skinny, Issue 121, October 2015: 51