The Head of Barbie Antoinette

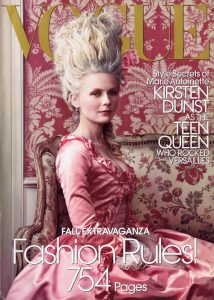

Cover of American Vogue, September 2006

The American artist Karen Kilimnik, who depicts bourgeois fantasies of aristocratic ‘decadence,’ has been hailed as ‘frothy, fun and the antithesis of everything great art should be’ (Neal, 2007: 100). Her portraits of movie-stars and celebrities posed as fairy tale characters and ancien-regime aristocrats include an image of the global heiress Paris Hilton in the guise of Marie Antoinette – ‘the teen queen who rocked versailles’ according to American Vogue (Vogue ed., 2006), though history knows her as a monstrous figure of decadence (a profligate spendthrift at a time of national bankruptcy) or a tragic scapegoat for the failures of the pre-revolution monarchy. Clichés both malevolent and tragic fade from Kilimnik’s and Sophia Coppola’s respective interpretations in which extravagance appears as a form of creative rebellion—‘the party that started the revolution’ as the poster-art for Coppola’s film exclaimed! The latter unfolds like an epic-scaled pop-video (the life of an 18th century ‘It Girl’); with not a severed head in sight and little allusion to the hardships of the peasant class. Whatever we might say about these historical blind-spots (Coppola’s Antoinette, though, appeared prior to the global economic crisis), there is no denying their negation of dramatic interest, suggesting that unchecked frivolity is as fatal to art’s powers of absorption as it is to its ethics. A similar candy-coated torpor infects Kilimnik’s practice which Donald Kuspit described as ‘hand-me down populism, a populism that has become so routine, even art-slumming populists find it boring’ (Kuspit, 2008: 8-9).

Karen Kilimnik, Marie Antoinette out for a walk at her Petite Hermitage, 1750, 2006

Edmund Burke would have had no difficulty explaining this deficiency; according to Burke: ‘there is no spectacle we so eagerly pursue, as that of some uncommon and grievous calamity; so that whether the misfortune is before our eyes or whether they are turned back to it in history, it always touches with delight’ (Burke, 2006: 125). And though some artists justify their shallowness, evoking Warhol as a precedent, this analogy scants the broad range (tonally and in terms of subject) of Warhol’s prolific practice (as the ‘crash’ paintings –and the more sepulchral of the ‘Marilyns’ – testify). Warhol’s true precedent in this regard is not Marcel Duchamp but Francesco Goya whose ouevre ranged from scenes of frothy superficiality and glamour (in his society and royal portraits) to the more stygian Capricchos and the Black Paintings. It is a cliché that political art aims towards an impression of scientific detachment; Goya’s work is in some sense ironically detached (alienated) from its own subject because it is so beautiful in form. In a number of the paintings, acute observation of light and surface is prescient enough to trigger memories of felt phenomena: air, flesh, stone, silk, blood – this is what gives the depiction of human tragedy its acute ‘viscerality’, no doubt. But Goya’s renderings can also be close-to-ornamental in their sparkling prettiness; the depiction of a satin dress crumpled in the mud or light pressing against the wall of a cave are as poignantly lovely in the image of two bandits raping and killing a woman as in the titillating Maja‘s and the weird portraits of The Duchess of Alba.

Jacques-Louis David, Marie Antoinette on Her Way to the Guillotine, 1793

The French Revolution was of course, the ‘party’ that started the romantic sublime after the cool geometry of neo-classicism—the latter part of of Marie Antoinette’s life-history does read like an especially saedian gothic novel. Coppola’s Antoinette lacks the very ingredient that, according to Burke, would give its pleasures piquancy (the spectacle of pain); the interminable frolicking of the aristocrats at le Petit Trianon is denuded rather than enhanced by the guillotine’s absence. Far from letting her audience have their cake and eat it (drowning out the noise of the Terror with her retro-pop soundtrack), Coppola gives them ‘brioche’ devoid of flavour. Perhaps I’m missing the point however. Perhaps it is Coppola’s (and Kilimnik’s) real intention to negate the scabrous pleasure of the Burkian mode (that Hammer-Horror cliché), in favour of the Duchampian sublime of ennuie, which ‘tragedy’ or even ‘incident’ would relieve. The ‘visceral’ is after all no less tokenistic in our jaded epoch than kitsch embraced in a spirit of irony. And if the spectacle of suffering is essential to ‘human-interest’, then what do we make of Jane Austen (that anomalous daughter of the eighteenth-century sublime) whose largest traumas puttered out behind the gilt edges of porcelain cups?

REFERENCES:

Burke, Edmund. ‘Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful’. in The Gothic Reader. A Critical Anthology. ed. Martin Myrone. (London: Tate, 2006). pp. 123-133.

Kuspit, Donald. ‘The Dregs of Modernism or Cleverness out of Control; The Whitney Biennial, 2008.’ Art New England. v. 29 no.5 (August/ September 2008). pp. 8-9.

Neal, Jane. ‘Karen Kilimnik: Serpentine Gallery.’ Modern Painters (May 2007). p. 100.

Vogue Editorial. Cover blurb. Vogue (September 2006).