‘The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods’: A Surrealist Awakening

Gustave Doré, Illustration for Charles Perrault’s ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ in Les Contes de Perrault (one of six engravings), 1867.

I am a painter and writer who has lived in Glasgow for more than twenty-five years. My ongoing interest in fairy tales and Surrealism has been nourished by that context—notably through dialogue with the Scottish writer and art historian, Catriona McAra, whom you heard speak today and who has written extensively on these subjects. As McAra has shown, through her perceptive analysis of the work of Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington, the ‘surrealist fairy tale’ is a hybrid genre that subverts the reader’s (or the viewer’s) expectations, bringing about a contradictory relation of ‘text’ and ‘image’.

In the summer of 2024, I began making a series of 26 illustrations to Charles Perrault’s ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ the frequently censored baroque version of the story more commonly known as ‘Sleeping Beauty’ (first published in 1697).

Intended for both an exhibition and an artist book, these works stage a material encounter of surrealist aesthetics and the literary fairy tale. Taking the form of watercolour paintings derived from 1980s-era magazine-pages and film-stills, these images are counterpoised to a well-known story.

***

The brainchild of Charles Perrault, a French civil-servant and philosopher, who had served at the court of Louis XIV and participated in the ‘Quarrel of Ancients and Moderns’, ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ (‘The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods’) was first published in his seminal collection, Histoires ou Contes de Temps Passé. Along with other tales in the collection such as ‘Cinderella’, and ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ played a key role in the (imperfect) historical process of ‘civilising’ fairy tales. As the Marxist folklorist Jack Zipes describes this process, the literary appropriation of fairy tales (by writers such as Perrault) from the late 17th century onwards, sublimated their erotic and political content (their latent ‘revolutionary’ fantasies):

At the beginning, the literary fairy tales were written and published for adults, and though they were intended to reinforce the mores and values of French civilité, they were so symbolic and could be read on so many different levels that they were considered somewhat dangerous: social behaviour could not be totally dictated, prescribed, and controlled through the fairy tale, and there were subversive features in language and theme. This is one of the reasons that fairy tales were not particularly approved for children. (Zipes,1995: 25)

The idea of a repressed content lurking within fairy tales, which has the potential to be ‘re-articulated’ through close reading or interpretation through other media, has informed many critical studies. My own project is a direct response to Lewis C. Seifert’s essay ‘Queer Time in Charles Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty”’ (2015)—concerned with how Perrault’s tale disrupts chronological time ’. As Seifert argues: ‘By deviating from the ordered sequence of chrononormative time, fairy tales can open a space for imagining other ways of being and desiring’ (Seifert, 2015: 24). As he writes:

Making the past live in the present is of course the central theme of ‘Sleeping Beauty’ […] the princess, thanks to her hundred-year sleep, is a living anachronism […] (Seifert, 2015: 25)

.

…the narrative suggests that […] the past will necessarily assume multiple guises, multiple narrative contours, in the present. But it also—and especially—announces that erotic desire that brings the past into the present. (Seifert, 2015: 28).

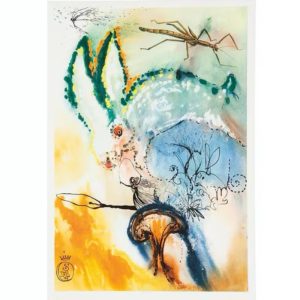

Salvador Dalí, illustration to Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Maecenas Press-Random House, New York, 1969. Image © Christie’s.

The political reimagining of fairy tales has not, of course, been limited to scholars of various disciplines. There has been a long tradition of visual artists depicting fairy tales obliquely (often using surrealist techniques). Examples of this approach include Salvador Dalí’s illustrations for Alice in Wonderland (a favoured text of the Surrealists), Cindy Sherman’s photographic tableaux for Fitcher’s Bird (a story by the Brothers Grimm), and Paula Rego’s ‘Snow White’ drawings (commissioned for the Hayward exhibition ‘Spellbound: Art and Film’).

Based on these revisionist approaches, it might be possible to argue for a certain affinity between fairy tales and Surrealism. But this is far from a straightforward alliance. André Breton (the French founder of the Surrealist movement) did not have unalloyed respect for fairy tales. He found them ‘puerile’ and conformist; these stories were ‘addressed to children’, and as such they could not substantially influence the adult mind with their fantastic visions (Breton, 2010: 15). He held out hope that fairy tales could be ‘written for adults, fairy tales still almost blue’ (Breton, 2010: 16).

Coming from another discipline (that of folk-and-fairy-tale studies), the writer and mythographer, Marina Warner, has acknowledged the vexed relationship of these two genres of the fantastic. As she suggests (In her book, From the Beast to the Blonde, 1994) there is a connection between these two expressions of ‘the marvellous,’ emerging in a dialectical approach to ‘dreams and ‘reality’. In fairy tales, ‘dreaming gives pleasure in its own right’ but ‘also represents a practical dimension to the imagination, an aspect of the faculty of thought, and can unlock social and public possibilities’ (Warner, 1994: xvi). She gives special emphasis to women artists connected with (and yet marginalised by) the movement (such as Leonora Carrington and Meret Oppenheim), whom she regards as modern fairy tale ‘tellers’ (see Warner, 1994: 384-5).

Following this thread, in her 2013 essay, ‘Sadeian Women,’ McAra invokes the post-modern writer of fairy tales, Angela Carter, who also translated and adapted Perrault’s tales (‘Sleeping Beauty’ among them). Carter was vividly inspired by the ‘female Surrealist practitioners’ who ‘would go on to outlive her’: such as Carrington (McAra, 2013: 72). In The Bloody Chamber (her infamous subversion of Perrault), she often deployed surrealist imagery; notably in her gothic reworking of ‘Sleeping Beauty’:

She is herself a haunted house. She does not possess herself; her ancestors sometimes come and peer out of the windows of her eyes and that is very frightening. She has the mysterious solitude of ambiguous states; she hovers in a no-man’s land between life and death, sleeping and waking, behind the hedge of spiked flowers, Nosferatu’s sanguinary rosebud. (Carter, 1981: 103)

***

My own practice emphasises the role of visual material in shaping the viewer’s experience of these contradictions. The methods I used to illustrate ‘Sleeping Beauty’ are inspired by Hal Foster’s analysis of Max Ernst’s collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (1934), a famous work of Surrealism, made from cut up engravings to nineteenth-century murder stories. As Foster observes (in his book Compulsive Beauty), Ernst’s process of cutting and re-assemblage ‘articulates’ the psychological and political content repressed in his source material:

Many of the sources are overtly melodramatic. Several images in Une Semaine de bonté are based on Jules Marey illustrations for Les Damnées de Paris, an 1883 novel of murder and mahem. These illustrations depict drames de passion […] In his appropriation Ernst relocates these particular scenes in psychic reality through the substitution of surrealist figures of the unconscious […] This transformation only articulates what is implicit in the found illustrations, for melodrama is a genre already given over to the unconscious, a genre in which repressed desires are hysterically expressed. (Foster, 1997: 177)

My own project will test whether (in our current context) an equivalent method can have the same effect when deployed as illustration’.

Following Ernst’s use of 1880’s book engravings (that were 40-50 years out of date when he appropriated them for his collage-novel), I made use of magazine images and film-stills dating from a period corresponding with my own childhood.

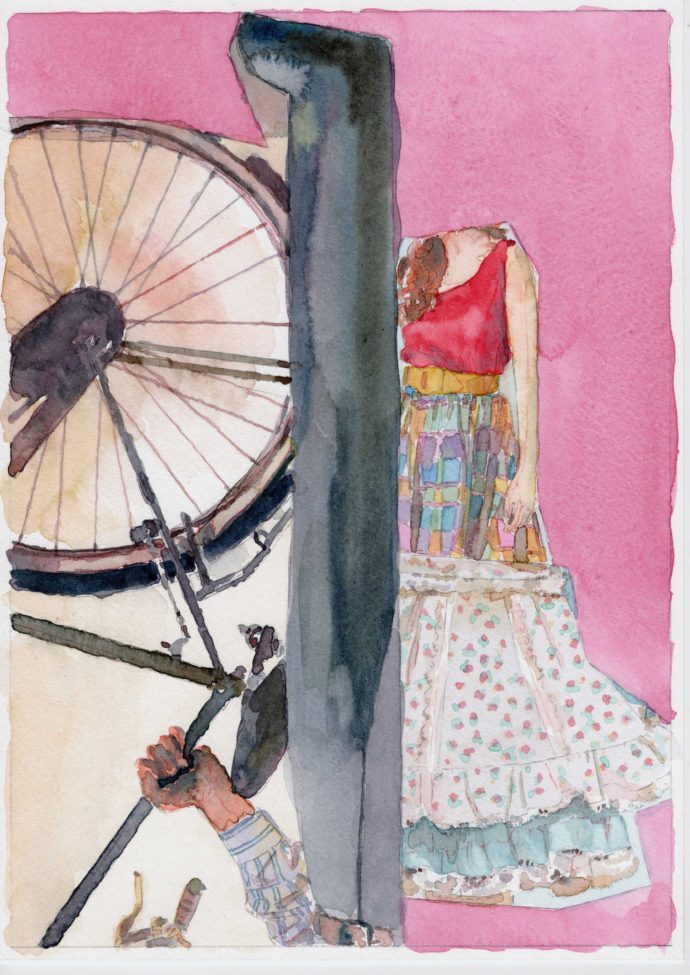

After cutting up these images and gluing them to sheets of coloured paper (in new arrangements), I transcribed them as watercolour paintings, aiming towards a visual hybrid of surrealist collage and “Golden Age” book illustration. I worked as intuitively as possible, trying to avoid any pre-conceived notion of how to ‘represent’ the story. Sometimes the illustrations parallel what is being described in the text; elsewhere the relationship of text and image is more mysterious and contradictory.

Across these images, quirks and anomalies occur—due to the fragmentary nature of collage and the obvious anachronistic effect of using late-capitalist media to illustrate a 17th-century story. This approach is in line with Ernst’s fragmentary use of old-fashioned imagery and with Siefert’s view that ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ is, at heart, concerned with disrupting normative time, that the story’s purpose is to show the ‘multiple narrative contours’ that the past will assume in the present. This is not to mention the interpretive limitations imposed by my source material: there are no spindles or thorns in this depiction of the story; instead men’s ties, telephones, bicycle wheels, replace the erotic and fateful (magic) symbols of the original.

These non-sequiturs are welcome, arising from my intention to utilise the chance methods of Surrealism as a form of fairy tale illustration, to observe what ‘spaces for imagining’, what ‘other ways of being and desiring’ might arise from this interpretive method. Through this approach I aim towards a rigorous (yet lucid) framework through which to address the discursive, theoretical and artistic contexts of the fairy tale as an (anti-)surrealist genre.

Laurence Figgis, 2025

Laurence Figgis, “She entered a little garret, where an honest old woman was sitting by herself with her distaff and spindle,” (illustration to ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’), 2024, watercolour on paper, 297 x 207 mm (Copyright Laurence Figgis).

References and Further Reading

Breton, A. (2010), Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, 5th ed., (Michigan: University of Michigan Press).

Carter, A. (1981), The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories, (London: Penguin).

Foster, H. (1997), Compulsive Beauty, 3rd ed., (Cambridge: Mass.; London: MIT Press).

Hopkins, D. (2021), Dark Toys: Surrealism and the Culture of Childhood, (New Haven, Yale University Press).

McAra, C. (2013), ‘Sadeian Women: Erotic Violence in the Surrealist Spectacle’, in Violence and the Limits of Representation, Matthews G., Goodman S. (eds), (London: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 69-89.

Perrault, C. (1991), ‘The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods,’ in Beauties Beasts and Enchantment: Classic French Fairy Tales, ed. and trans. Jack Zipes (London; New York: Meridian), pp. 44-51.

Pointon, M. (1996), ‘Paula Rego’, in Spellbound: Art and Film, (London: Hayward Gallery, British Film Institute).

Sherman, C., Grimm Brothers (1992), Fitcher’s Bird, (New York: Rizzoli).

Seifert, L. C. (2015), ‘Queer Time in Charles Perrault’s “Sleeping Beauty”’, Marvels & Tales, Vol.29 No.1, 21-41.

Warner, M. (1994), From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers,(London: Chatto and Windus).

Zipes, J. (1995), ‘Breaking the Disney Spell’, in From Mouse to Mermaid, the Politics of Film, Gender and Culture, ed. Elizabeth Bell, Lynda Haas, and Laura Sells, (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press): 21-42.

This paper was delivered at the Art & Text Conference (Scottish Society of Art History), National Library of Scotland Edinburgh, 7th February 2025.