Jessie Whitely in Conversation with Laurence Figgis

CASTRO introduces Artist Talks: a nine-event series which offers the chance to hear from young artists through learning and discussing about their practice. The Talks aim to connect the practice of the artists currently on the Studio Program, external professionals and the public.

In conversation with a professional of their choice, each participating artist will discuss themes in their work as well as current issues in contemporary art. As all events in the CASTRO Public Program, the talk will open up to a round table discussion with the public.

Jessie Whiteley is a Glasgow based artist. Her current work is primarily painting, drawing and comics, as well as collaborative projects.

J: I invited Laurie to do this talk with me because I am interested in how his work deals with human practices and behavior—narrative, costume, language etc.. These were things I was thinking about in my own work, particularly with regard to painting and writing. First Laurie is going to do a reading of one of his poems— I don’t know if there’s anything you wanted to say about it Laurie?

L: The poem is titled ‘Objet d’Art’, referencing the term used when speaking of a particularly rarified object. I was partly inspired by a famous image from ‘Snow White’. I was thinking about the moment at the end of the story when she comes back to life. If you are familiar with the fairy tale (by the Brothers Grimm), she is not kissed—there’s a convulsion; they are carrying the coffin away and, when they drop the coffin, she regurgitates the poison.

The artist I wrote the poem for (Steven Grainger) was about to do an exhibition in Australia. There was a lot of worry about getting the artwork to its destination. If you’ve ever done an exhibition where you have to transport work, you know you always worry about it breaking in transit.

Somehow these two ideas merged. I’m really interested in fictions and narratives that capture our relationship to objects, as a parallel way of talking about our relationship to other people. How trying to imagine yourself into someone else’s situation can be like trying to imagine yourself into the “mind” of an object; how art objects, in particular, have a subjectivity or soul; how in trying to relate to them, we start to imagine them thinking or speaking.

The act of writing about an object can operate in two ways that interest me. We can imagine that we are trying to make the object speak. It can also be the case that we are speaking for the object—and there’s a strange, inherent violence in that process. That’s is a very brief summary of what I was trying to engage with (in the poem). But I thought it was a nice way to begin talking about narrative structures within and around art objects—and how that relates to the idea of art communicating something. Is it possible for an object—for example a painting—to communicate? Is that what the artist would like the artwork to do? Or is the artwork always silent? Does it resist this act of communication?

This is a good place to begin. We came up with some basic questions that we can ask each other as a way of starting the conversation.

I’m going to start with the first question: Jessie, could say something about the process of making narrative structures in your work? For example, do you begin with a particular story in mind or does the story take shape as the painting evolves? And how much of a role does accident or intuition play in the development of narrative in your paintings?

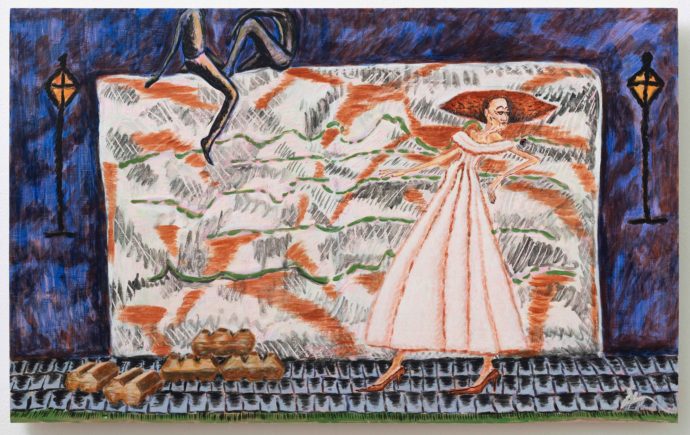

Jessie Whitely, As far as I know, 2019, egg tempera on board, 100 x 60 cm, © Jessie Whitely

J: [referring to an image on the projection] Well I think, particularly with doing a drawing like this, or maybe the first paintings in a body of work, spontaneous “starts” and accidents would definitely lead the way. Often, I would make rhythmic sorts of drawing marks, to start off, then see what kind of imagery I find within those marks. Maybe, say in this one, I start to see (in the marks in the middle) a wedding dress. And then you have an image, for the next connection to be made. Then it becomes a kind of building of ideas, one thing leads to another— rather than a whole vision of how something might be. But then maybe then I will have more of an idea of what I want to do—like ‘I want to do a painting of people in public’ (people walking about, people interacting with each other)—I want there to be something to do with the way people are looking at each other, thinking about viewpoints and perspectives, in relation to a worldview. Then after I’ve got over the start of the framework, it’s about building it through compositional things—like this colour means the next colour should be this. The building of the composition is what I then become interested in.

L: Do you ever start with a whole series of colours? Or do you lay one colour down and start reacting to that?

J: Well, I think with egg tempera paint (which I have been using for these works), you kind of use one colour at a time, and there’s a limited palette that I am working with. So, it will tend to be like: just doing green for this time, just doing red for that time. I think something about that break-down of colours that you get through the quality of egg tempera paint (which doesn’t mix to a tonal gradient) can enable you do something with the rhythm and composition. And this can act as a tool to make things connect to each other in a way they wouldn’t necessarily if things weren’t so separated. Like how this man (in the painting) is made out of the same thing as the woman’s bikini bottoms (both blue) and this man’s nose is made of the same thing as the background. These things can make connections though the fact that they are made of the same substance. I think that this makes some sort of narrative, in a way— just by the process of visual linking.

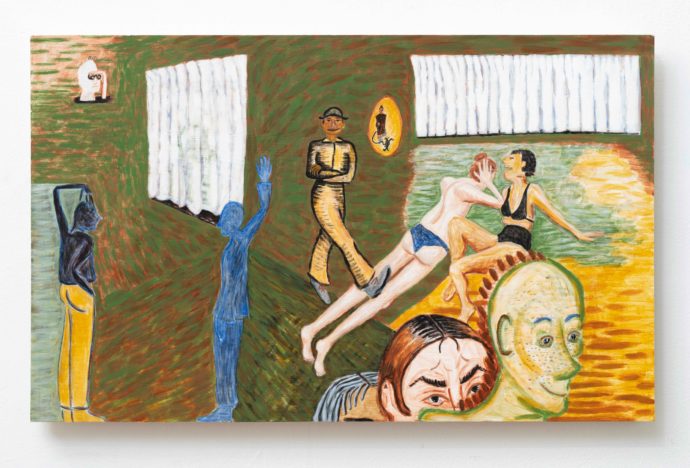

Jessie Whitely, As far as possible, 2019, egg tempera on board, © Jessie Whitely

L: I’m quite interested in the mood of the paintings—and maybe that comes across quite strongly for me in the colour as well as in the composition. I like how, as I move across the painting, the temperature changes. Here, there are figures on a beach. Then as you move across—well we both live in Glasgow (and we were talking about the Glasgow climate)—it makes me think of that sort of climate, its coldness; or here it makes me think of an interior. Then there’s this red underneath the cooler colours, which creates an interesting emotional narrative as you move across.

J: I guess I like to keep a sort of tension between hot and cold in a painting. I think particularly, in this one, I wanted to keep a tension to the sense of distance, and I think the temperatures do that to an extent. Also, where the focal point is, where the main characters are; wanting to keep those sorts of things moving, to keep shifting where you might rest at a subject-matter or point of view.

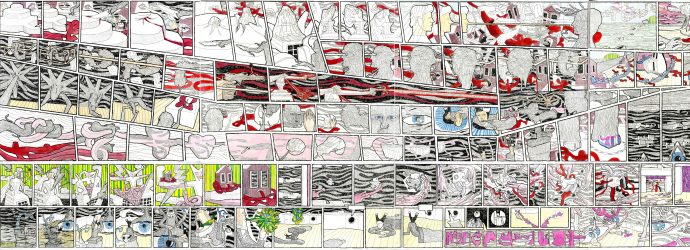

L: It reminds me a bit of one of my pieces—which I was telling Jessie about today. In the end it took 7 years to finish; not because I was working solidly (there were quite big breaks in between). But it’s a drawing that goes across smaller sheets of paper that join to make the whole thing. I did not begin with an overall sense of composition. I would start in one corner, then do bits in the middle. The drawing lets you know it is a narrative through its composition—this very obvious structure associated with storytelling, the sequential form—obviously referencing comic books. A lot of people asked me, “oh you must be really into comics”, but I had never actually read any. I wanted a way to deal with the space and the background. Because I have this interest in storytelling, I thought, well I’m going to use the “background” of the drawing to tell a narrative, and that made me use the whole space. It was like coming up with a narrative in order just to “fill up” the space, to give the painting its structure.

Laurence Figgis, The Great Macguffin (detail), 2005/2012, ink, crayon, gouache, watercolour on paper, 150 x 350 cm, ©Laurence Figgis

J: I remember you said it came from particular images of collaged figures you had done, but the direction of the narrative didn’t take form until you started?

L: It’s a bit like writing; the whole idea of writer’s block, where you can’t get flow of ideas to happen. But sometimes you won’t have that— you just sit down, and you make yourself start writing, and somehow it “comes out” on the page. This was an attempt at a similar approach with drawing. I got an idea of what would happen “next” through the process, the images changing as I went along. That happened quite intuitively. I would have certain images, maybe certain ideas from reading certain stories, but I didn’t have an idea of the “end” at the beginning. It came together as I made the piece.

J: I think not having an “end” and a “beginning”—that was why I might have shied away from thinking about narratives and stories in my work. Because it’s not how I work, and I didn’t like the idea of something with a “start, middle and end”—having a focal point. But maybe I’ve got over that, realizing that narrative is generally not quite like that—I can think about it a bit more.

L: The next question leads on from that quite nicely: we talked about language and the enjoyment of language. Do you think painting functions like a language or as a language: equivalent to spoken or written words?

J: I don’t think I see it as equivalent—because it’s a different thing. But I like to be influenced by language in painting as something separate. Maybe thinking about writing methods in relation to painting can be interesting—to make you do different things. Like wanting to think about “jokes”: how that works in a painting, thinking about double meaning. This painting is called ‘as far as you like’. I am titling this body of work with different endings to the phrase “as far as”: As far as possible, As far as I can see, As far as I can tell… I’m thinking about the slight differences in words or imagery that can mean something completely different or take you down a different path. That is something also to do with learning a bit of a foreign language—and also related to being bad at spelling. The way that words can mean something very different after a slight change. And how words and images are loaded with meaning and have all these connections; just how the slight change in sounds and move of your mouth (or small marks on a page) can mean alternative things. Somehow, I might be thinking about that, in the imagery I’m using.

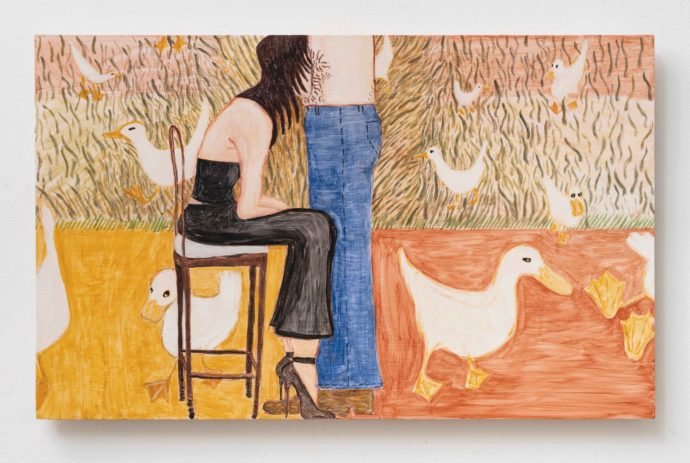

Jessie Whitely, As far as you like, 2020, egg tempera on board, 60 x 100 cm, © Jessie Whitely

L: There’s also repetition in this one—repetition but variation—which is how language works as well. It’s interesting; when you think about listening to a language you’re not familiar with; it can sound like a repetition of sounds; but it can be more enjoyable to hear, than when you know what the meaning is—like singing along to pop songs when you’re a child.

J: Yeah, it’s nice walking down the street [in Rome] and having a bit of space from the constant hearing of chitter chatter. I guess with repeating the duck image [referring to a painting in the slide] it makes you think about where the meaning lies. Is this the same duck repeated—or is it lots of different people or ducks?

L: Yeah, it’s interesting—I can almost imagine a sound as well: the sounds I would hear, if I was imagining a real situation with lots of ducks.

J: Like what sounds?

L: Like quack-quack! But also—when you look at them closely—they have their beaks closed. They could be paddling about silently.

J: And you how do you feel about these things?

L: For me the written side of my work and writing about other people’s practices relate to each other. When you think about the experience of going through art school, there’s a lot of pressure to be talking about art all the time. It can feel like you never stop talking—which is interesting in some respects. But I think, at some stage, I felt like working with language was a creative thing for me; and it was about an enjoyment of the form—not about analyzing or “explaining” a work. So, in a number of instances—even when writing about the work of another artist—I’ve written something like a poem or a fiction.

The term ekphrasis is an ancient Greek term, that refers to language evoking a visual experience—particularly an artwork. There are a lot of examples in fiction of artworks being described through language. Sometimes those objects are magical—like The Picture of Dorian Gray. That’s an interesting problem for fiction: if a writer “stops” to describe something; what a room is like—and starts talking about the colours etc.—does it stop the narrative? People might skip over these bits because they want to know what happens next.

J: I think I’ve realized, the kinds of narratives I like are the ones that mostly just ‘describe the room’. I like the ones that aren’t plot-driven so much; but just some things happening. I really liked reading Natalia Ginsberg’s Family Lexicon: the way it is built up from conversation, and events arise and go away with no build-up or explanation, things are passing by— it’s just momentary—things happening, and then they’re gone. These are the types of narratives that I’m excited by—maybe how I want things to happen in my work.

Bruegel, Pieter the Elder, Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, c.1555 oil on canvas, 73.5 x 112 cm, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels

L: There’s also a great tradition in fiction and poetry. There’s a famous William Carlos Williams poem, in response to Bruegel’s The fall of Icarus. W H Auden wrote a response to the same painting, a version of the Greek myth, in which Icarus wore wax wings close to the sun and fell into the sea and drowned. In the painting, you have a landscape with ships at sea, people going about their daily life; and only when you look very closely, you see a pair of legs sticking out of the water. And it’s a very dead-pan way of dealing with this tragic myth; how everything is carrying on while one person’s life is ending (in the corner of the painting). And so, the poetic responses talk about everything else that is going on in the painting—and then just mention the splash in the corner. It’s literature trying to engage with the visual—just as painting and sculpture has tried to engage with narrative in the past.

This leads on to the next question. Could you talk about any literature or film that you have been thinking about in relation to your work?

J: I’ve been listening to the New Yorker Poetry podcast a lot. There’s one episode where they’re talking about an Elisabeth Bishop poem called ‘The Moose’. In the podcast, the guest was suggesting it could be a metaphor for “a muse”—but the host was shutting it down, saying not everything has to be a metaphor. It’s a collection of imagery and things happening that relate to each other. There isn’t a more rational way to read into it—to tell you how things really are. I found it useful when thinking about my own work, building things up in a way that can be led by change and build from response. At the end of it, I might finish and be like: well what does it all mean?— what am I supposed to get from this? But it hasn’t got some overriding meaning; it has momentary meanings and things that have connections—and really that’s where it settles.

Question from the audience: that is what I find interesting in the works: how when we are taught to read at school, there’s always something about making sense, interpreting meaning, how to identify things. What is often interesting with regard to poems about paintings; they never really go somewhere, there are a lot of false starts, splutters, which builds up to something not fully explainable. Talking about language and painting—maybe what is interesting is the bridge of poetry: sort of making sense—but without explaining every point. I was wondering if you could focus more on your relationship to writing that breaks from structural conventions? Like in a poem you can break down and de construct language—the same way as (in the paintings) you are breaking down imagery.

J: Yes—that is what I have been enjoying about getting more into poetry; particularly these poets like Elizabeth Bishop and John Ashberry who deal with a language of everyday. It’s that breaking-down of everyday language: when I bring things up that mean things in my paintings, I want to link things—but break things down as well. I want to break down how things might—or might not—relate to each other.

L: That’s something that strikes me about a poem as well—how it works with rhythm—or when you might want to take a breath between stanzas. Things like rhythm and repetition can be useful ways to think about why you enjoy a painting, and how it evolves, and when you decide it is resolved.

J: Because, I guess, you want avoid settling the rhythm— settling the compositional things. You want to keep it at a place where it is disturbed. But how to ‘complete’ something—when things are up in the air.

L: This makes me think of Emily Dickinson— a poet who was misunderstood by her own publishers. She was interested in unsettled rhythm, unsettled meaning. In her famous existential poem, ‘There’s is a certain slant of light’ her original reads: ‘There’s a certain slant of light/ Winter afternoons—/ That oppresses, like the Heft/ Of cathedral tunes—’. The editors changed this to: ‘the weight of cathedral tunes’. I think it’s always important to read poems out load—and I don’t know if you can tell the difference—what this does? So ‘heft’ (rather than ‘weight’) doesn’t make strict sense or work fully in sense of meaning. But a heft—you think of this action, this movement of your mouth. There’s an interesting thing in poetry, where at certain times people have tried to conventionalise it—to make it slightly easier to digest.

J: It is interesting to think about the reading of it— and the movement of your mouth in saying ‘Heefft’—you can think about it in relation to making a mark (in a painting).

Question from the audience: Do you think much about dreams in your works?

J: Not directly to be honest— I tend to forget them when I wake up. Maybe more daydreams, things that are half-conscious. My dreams are usually worrying about something stupid. I think I’m more interested in the fantastical side of the everyday and the strangeness in mundane things—rather than the dream-works.

L: I similarly tend to forget my dreams—but I have a feeling when I do dream it tends to be about very ordinary things. “Magical” things don’t happen in my dreams— I don’t think.

Question from the audience: Can you say something about the different realities that you seem to deal with in your work?

J: I guess, I think about all these different realities existing in these spaces; all the people with their different viewpoints and realities—with singular perspectives on things, that you then try to comprehend within a worldview outside of your perspective; and the distortion that happens in that, and the strangeness in trying to imagine outside of yourself. That reminds me a bit of Peter Wachner’s writing, how he uses a singular perspective in stories that distorts things: the difference in trying to imagine lots of different perspectives and realities—not just one— how it can make things stranger than just imagining one viewpoint. Like in The Simpsons: how the story moves in a linear way; Homer goes to a cat store; the cat wins a beauty contest; Homer gets loads of money; he buys a speed boat. But—yes—I am thinking about layers of realities. Particularly with having a constant relationship to a phone—and online—which is so part of your everyday, it can feel like living in limbo.

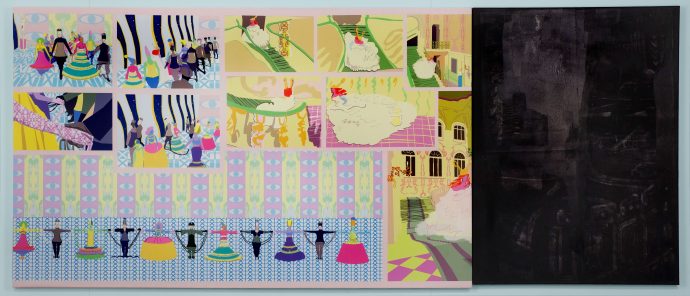

Question from the audience: Looking at The Great Macguffin (as far as I can tell) compared to some of your images before, the idea of a ‘frame-within-a-frame’ can create some kind of movement or story board. Could you say something more about that?

Rear Window, 1954, dir. Alfred Hitchcock (film still)

L: It reminds me of the Hitchcock film, Rear Window, which is also like my tenement flat in Glasgow, where the flats are all facing one another—so you can always watch your neighbours—you can watch someone going from room to room, see who is doing the washing up. The way this works compositionally is interesting. Hitchcock had a big set built, a replica of an East Village apartment courtyard. He apparently spoke to the actors through a walky-talky, telling them what to do, while he watched them from a distance. You see the narrative evolve through these apartment windows, which, to me, seem a bit like a filmstrip. It is a work of cinema—so it has that time-based narrative; but the narrative also moves across the surface like a painting. I think this is Hitchcock enjoying the surface of the screen. These little boxes (in my drawing) make me think about those windows.

J: It is nice, thinking about those flats in Glasgow, which always have a courtyard. You can just watch the figures moving between framed sections.

L: Glasgow is built on a grid-system as well. The streets are at right-angles to each other; it makes nice compositions.

J: Yeah— compositionally it’s lovely living in Glasgow!

Question from the audience: There is a difference with framing, I see Jessie’s work framing inside—or their being different scenes not framed at all; whereas, in Laurie’s work—from the ones you have shown us—the imagery is quite separate. Does it calm you to separate the frames?

L: Yeah, it must do! You don’t need these frames to separate things—or even to tell a story. So, it must say something—

J: But I guess it does deal with time in a more direct way than it could without it? Or—I guess—you do get those paintings from the early renaissance? Where there is a monk at the bottom of the hill, walking up the middle, and reaching the top—all in a singular image. You understand, it’s about time, through repetition.

L: I also really like Mondrian paintings—with their angular forms; but I’ve never been able to make an abstract painting—so maybe it’s about being jealous of people who can! Wanting secretly to make an abstract painting.

J: I think you have to have a certain temperament. This painting was trying to be abstract. It’s quite hard to know how to make it interesting. When you have a thing— like, “I want to do a cat”— you have a pattern to go off from.

Laurence Figgis, The Club-Grande, 2017, dye-sublimation print, collage, acrylic paint on canvas, 120 x 304 cm, ©Laurence Figgis