Twin Peaks / The Art Life

Twin Peaks, 1990, dir. David Lynch (still)

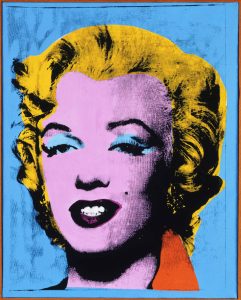

Possibly because my initial viewing of Twin Peaks: The Return (2017) coincided with my watching David Lynch: The Art Life (2016), I couldn’t help but be aware of the veiled allusions to creativity that occur throughout the wider series (including Seasons 1 & 2). It seems to me that much of the series’ imagery and symbolism relates closely to Lynch’s experience of making art, rather than necessarily to a bespoke mythology (though I don’t of course discount the theological significance of the “Lodge Lore” debated by countless fans). I also wonder whether the creative collaboration of David Lynch/Mark Frost derives from two contrasting views of the medium and form of television, one view emanating from painting (Lynch’s view), the other from literary fiction (Frost). In view of Lynch’s continued activity as a painter I am struck by the possibility that Twin Peaks may be referring to art history in addition to cinematic/ televisual references. (<<< SPOILERS AHEAD >>>). For example, in a public talk given in Glasgow in 2007 (to promote his TM foundation) Lynch specifically cited Francis Bacon as an influence. Both Judy/ The Experiment and Sam’s and Tracey’s mutilated corpses resemble Baconesque figures—and the New York crime scene has the look of a ‘collage’ (recalling the visceral hand-made style of Surrealist or Expressionist painting) rather than the smooth CGI to which we’ve become accustomed. Lynch’s and Frost’s mention of Marilyn Monroe (in relation to the genesis of the Laura Palmer mystery—see Bocko, 2014), recalls Andy Warhol, who repeated Monroe’s head-and-shoulder portrait across a series of canvases; much in the same way that Lynch (and other directors) repeat the high-school portrait of Laura in numerous scenes and episodes (almost exhausting the image). I wonder, if Warhol had lived long enough to view Twin Peaks, he might have been inspired to make a silk-screen of Laura’s portrait too! Affectively Laura’s image is already ‘serialized’ within the visual narrative, as one of many still images and objects fetishized in the animate world of Twin Peaks.

Andy Warhol, Blue Marilyn, 1962, acrylic and screen-print ink on canvas, 50.5 x 40.3 cm, Princeton University Art Museum

As many fans will know, Lynch was first inspired to make film, during his early days as a student painter, when regarding a work-in-progress, his canvas ‘moved’ (due to some external influence) or he simply imagined it moving. This primary creative fantasy, recurs in Twin Peaks—as just one example of a ‘myth of origins’ or ‘creation myth’ that the show explores (including, and often in conjunction with, a myth of ‘original sin’). The desire to make still objects ‘move’ drives the visual mystery of Twin Peaks, whether in relation to Laura’s corpse, Laura’s portrait, the video footage of Laura (that can be paused, rewound, speeded-up at will), the stag’s head trophy that has ‘fallen down’ next to the safety-deposit boxes, Margaret Lanterman’s log, the ceiling fan, the record-player, the red room (where footage goes backwards), Nadine Hurley’s drape runners, the ‘scrubbing’ footage of the woodsmen in the ‘convenience store’, the red velvet drapes which ‘come to life’ in Season 3. The idea that film, video, and (by extension television) are, at base-level composed of static frames that give the illusion of movement (and hence of life) seems morbidly present in the visual texture of Twin Peaks.

Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), dir. David Lynch (still)

Another fundamental concern of painting is the desire to endow flat images with three-dimensional volume (this concern has also been integral to cinema, as we know from Greg Toland’s collaboration with Orson Wells, among others). When Lynch speaks of wanting to go ‘deeper into a darkness’ (or words to that effect) he uses a formal language, associated with painting, to articulate that psychological or ethical dilemma. The painter’s frustrated desire to transcend the flatness of the picture plane/ television screen is often expressed in terms of violence in Twin Peaks. Recall the terrifying moment in Season 2, when Bob climbs over the coffee table and sticks his face in the frame, almost as if he would burst through the television and into the hapless viewer’s world. Or think of poor Madeline Ferguson having her head smashed into a glass-framed picture on the wall of the Palmer house (incidentally a map of Missoula Montana, Lynch’s birth town—another place of ‘origins’). Madeline’s death recalls the earlier scene of violence done to a framed picture, when Leland smashes Laura’s portrait after grimly trying to animate it (by ‘dancing with’ it), then rubs blood into the fragments. This in turn looks forward to Sarah’s frenzied ‘stabbing’ of Laura’s portrait in Season 3, and at least three other moments I can recall in which glass screens (containing pictures of sorts) are smashed in in conjunction with violence done to the human body: when Leland bludgeons the television screen prior to murdering Tersesa Banks in Fire Walk With Me; when Cooper smashes his head into Bob’s reflection (in the Season 2 finale); and when ‘the Experiment’ breaks through the glass box to annihilate Sam and Tracey (in equally bloody fashion). What are we to make of this provocative analogy of the creative and the destructive act?

Vertigo, 1958, dir. Alfred Hitchcock (film still)

Laura’s portrait echoes both the painting of her namesake, in Otto Preminger’s film Laura (1944), and the painting of Carlotta Valdes that fascinates (or appears to fascinate) Judy/ Madeline in Vertigo (1958) (see Bocko, 2014). In all these narratives, portraits feature as a key aspect of the violence done to women (both metaphorical and actual). I am reminded of Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s book The Madwoman in the Attic in which they describe the patriarchal myths of creativity that exclude or objectify women. Gilbert and Gubar make particular reference to ‘Snow White’ (another dead young woman enclosed behind glass—or ‘wrapped in’ transparent material), another woman who is —as they put it—killed ‘into art’ (Gilbert and Gubar, 2000:36). Twin Peaks is not explicitly a story about making art, but this makes it all the more intriguing to consider in respect of creativity. Freud insisted that the whole of our material world encodes sex. For me, art is the underlying obsession of Twin Peaks. There are no actual artists in the series (male or female), but many of the characters engage in activity that could be described as creative. Cooper is most successful when responding intuitively to clues and deploying unconventional methods; Wyndham Earle is the archetypal ‘evil genius’ of disguise and theatrical plotting; Laura, writing in her diary, is one kind of artist; Harold tending his orchids is another; Nadine obsessing over her silent drapes is surely the most sophisticated of conceptual artists—as is Doctor Jacoby when he sprays his metaphorical shit-shovellers gold; Norma is an artist in the culinary field (if we believe the ecstatic reception of her pies and coffee); Audrey works sculptural wonders with that cherry stalk… I love the idea, suggested by the movie blogger and critic Joel Bocko, that when Sam watches the glass box, he is really watching television, and in that sense, directly parallels the viewer (see Bocko, 2017). But I also like the possibility that Sam may be an artist, looking at his own painting. It strikes me that the cavernous New York apartment, where the glass box is housed, is an idealised (almost archetypal) representation of a contemporary artist’s studio. I like to think that, when Sam gets up to change lenses on the camera, before resuming his seat, he is equivalent to a painter making small adjustments to his work before standing back to see the results. Obsessive ‘looking’ is essential to the craft of painting. And I like to think that Sam is a young David Lynch, alone in his studio, staring at his painting, as it slowly progresses, and willing, hoping that it will ‘move’.

Twin Peaks: The Return, 2017, dir. David Lynch (still)

When Tracey enters the room, she behaves in manner that suggests how family members or friends might behave, when an artist reluctantly lets them into their sanctuary to view a work-in-progress, and they respond with perplexity and bemusement, demanding a rational explanation that the artist cannot supply. Her essential function is to distract Sam (the artist) away from his important work, and the results are fatal both to the artist, and to the glass box (i.e. the work itself and the mysterious knowledge that it might confer on the viewer/ maker). Tracey’s extremely attractive, charismatic personality (as portrayed by the actor Madeline Zima) complicates this misogynist trope (the tortured male artist blaming the women in his life for distracting him from his ‘higher purpose’). Tracey embodies, for me, Lynch’s complex view of the relationship of life and art. Life is not the negative alternative to art that must be ignored. Life nourishes art, just as art can stultify or deaden life— just as the artist’s life can be in danger of isolation and irrelevance. Lynch is clearly sensitive to the fragility of art when subject to brutal corporate interference (the candid subject-matter of Mulholland Drive, 2001). But I wonder if he also holds out any hope for a reconciliation of life and art. Is this desire a part of the underlying search that drives the mystery of Twin Peaks? And if ‘the art life’ is in some respects a hopeful or celebratory concept, then why does it manifest so often in images of violence? And why are images of women so often the raw material of this destructive force?

A version of this text was submitted to the Lost in the Movies Patreon Podcast and read aloud as part of the ‘listener feedback’ for ‘Episode 30: Twin Peaks Season 3 Re-watch…‘ (23rd July 2018).

References

Bocko, Joel. ‘Twin Peaks: The Return Parts 1 & 2′. 2017. Lost in the Movies. http://www.lostinthemovies.com/2017/05/twin-peaks-return-my-log-has-message.html (retrieved 30.10.2018)

________.Journey Through Twin Peaks: Chapter 6‘:Who is Laura Palmer’. 2014. (video essay). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Ai_jEi7GjM. (retrieved 30.10.2018)

Gilbert, Sandra M. & Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth Century Literary Imagination. 2nd ed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.