Pearlescence and Patience: some thoughts on writing for ‘The Flight of O’

I’ll start by introducing the background of my general approach to art-writing, prior to addressing how I dealt with the specific challenge of writing about Zoe Williams’ work. I came to creative and fictional writing from a background of writing criticism, and to critical writing from a background of making visual art, which I continue to do alongside my literary practice. I’m an unusual example of a visual artist who doesn’t mind writing and talking about art. But whilst this is an advantage in some respects it can also be a challenge. The attraction to language in the context of visual art can, because of it’s association with explanation or interpretation, threaten to circumscribe the autonomous development of the visual outside functional or rational parameters. It can be hard to avoid making work that simply illustrates a preconceived idea or theory. One of the ways that I dealt with this conflict in my own practice was to subject language itself to an irrational transformation, drawing inspiration from literary and concrete poetry, as well as dadaist and surrealist experiments with language. This approach has also informed my role as an art-writer when responding to other practices.

Last year I was commissioned to write a press-release and gallery text for Lorna Macintyre’s exhibition ‘Sentences Not Only Words’ at Mary Mary in Glasgow. Her only specification was that the text should avoid “explaining” the work directly but should operate as a more suggestive and lyrical sub-text to the exhibited works. My initial source of inspiration was one of the artist’s own titles which itself derived from an inscription found in the interior of Rosslin chapel in Midlothian in Scotland: ‘wine is strong, a king is stronger, women are stronger still, but truth conquers all’. However because the process of photography seemed aesthetically and symbolically pertinent to Macintyre’s body of work I also tried to capture the sense of an image emerging and dissolving in a photographic dark-room. The whole of the finished poem was structured around this image:

Sentences Not Only Words

The lead shadows cleared again

and something that was not a bird

moved slowly through the restless tones:

a long white line that rolled around

the tree-forms on the plate,

and rose and broke the surface.

The waves straightened themselves out

in the water and kept still.

The King sighed. He spoke of veritas –,

and wooed the stone falsely,

and exhumed his vulgar money from the earth.

‘Are we then to suppose

that silver is dead, the crow is a warning;

the white one means death?’

Four days later,

the flowers on the patterned paper walls

(of Madam’s room) changed colour;

violet in the night

where there had been a rotting moon.

As you can see there are definite symbolic echoes between my text and Macintyre’s works but these are rendered in such a way as to avoid a straight-forward conceptual reading. Similarly when it came to producing the publication text for Zoe Williams, the idea was to create a semi-autonomous work of literature.

Peau D’Âne, 1971, dir. Jacques Demy (film still).

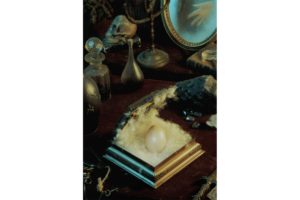

When visiting Zoe’s studio and discussing her creative and thought processes as well as her sources of influence I felt that the fairy tale would be an ideal form through which to extrapolate her work. My choice came about in response to the types of materials used or emulated in Zoe’s work, such as pearl, marble, ivory or mirrored glass which immediately suggested a fairy tale lexicon, whilst also creating a link to bespoke crafted objects of high-end commodity culture. It is the raison d’être of fairy tales to combine animist fantasies and scenes of brutal violence with images of conspicuous consumption. In writing the text I dew on two specific stories both of which concern the flight from authority, and which thereby provided a direct link with Zoe’s title, ‘The Flight of O’. ‘Donkeyskin’ by Charles Perrault (which was filmed by Jacques Demy in 1970 with Catherine Deneuve in the title role) concerns a princess who disguises herself as a slattern to avoid her father’s incestuous marriage proposal. ‘Fitcher’s Bird’, is a brothers Grimm story, a Germanic variant on the classic tale of ‘Blue Beard’, in which the heroine discovers the mutilated bodies of her husband’s previous wives (the story was illustrated with photographs by Cindy Sherman in a 1992 edition). Both tales are concerned with objects as a source of talismanic power and this again seemed relevant to Zoe’s work.

Cindy Sherman, illustration to Fitcher’s Bird, 1992

The following extract comes from the ‘Fitcher’s Bird’:

…he said: “I have to take a journey and must leave you alone for a short while. Here are the keys to the house. You can go anywhere you want and look around at everything, but don’t go into the room that this little key opens. I forbid it under penalty of death.”

He also gave her an egg and said: “Carry it with you wherever you go, because if it gets lost, something terrible will happen”. She took the keys and the egg and promised to do exactly what he had said. After he left, she went over the house from top to bottom, taking a good look at everything. The rooms glittered with silver and gold, and it seemed to her that she had never before seen such magnificence. Finally she came to the forbidden door and planned to walk right by it, but curiosity got the better of her. She examined the key, and it was just like the others. When she put it in the lock and turned it just a little bit, the door sprang open.

But what did she see when she entered! In the middle of the room was a large, bloody basin filled with dead people who had been chopped to pieces…She was so horrified that she dropped the egg she was holding into the basin. She took it right out and wiped off the blood, but to no avail, for the stain immediately returned. She wiped it and scraped at it, but it just wouldn’t come off. (Grimm, 1999: 149)

When writing the text for Zoe, it helped me to think of her exhibition as a collection of props which hinted at absent human characters. I saw the role of the text as a drama which would bring these invisible entities to life. However it was important for me to retain the ambiguous relationship of these invoked human presences—the players in the narrative—to objects and artifacts. The idea of transforming the human body into a commodity is central to fairy tales both as a source of sublime erotic fantasy and violent dread, for to identify with the world of things is to identify with the world of the dead and the undead and so to engage with uncanny narratives about objects and totems which “return” the viewer’s gaze. This death-driven eroticism is often embodied in objects which mirror the violence done to the human body. This violent fetishism relates to surrealist practice (including feminist-orientated surrealism) and the avant-garde pornography of Georges Bataille which was an important influence on Zoe’s work.

This paper was delivered at Spike Island Bristol as part of the event, “Laurence Figgis and David Punter respond to ‘The Flight of O'” (26th May 2010). You can read the short story, ‘Pearlescence and Patience,’ here.

REFERENCES:

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. ‘Fitcher’s Bird’. in Tartar, Maria (ed.). The Classic Fairy Tales. (New York; London: Norton, 1999).